This Bad Boy Can Fit So Much Cold War Arts Funding

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/40/e7/40e76a5f-ada9-45da-9dfb-e9824647380e/nov2015_d05_fourthmole-web-resize-v2.jpg)

London, May 17, 1985: Oleg Gordievsky was at the elevation of his career. A skilled intelligence officer, he had been promoted a few months before to rezident, or chief, of the KGB station in the British capital letter. Moscow seemed to have no inkling he'd been secretly working for MI6, the British secret intelligence service, for xi years.

That Friday, Gordievsky received a cable ordering him to written report to Moscow "urgently" to ostend his promotion and encounter with the KGB'southward two highest officials. "Cold fear started to run down my back," he told me. "Because I knew it was a death sentence."

He'd been back at headquarters only iv months earlier, and all seemed well. At present, he feared, the KGB'south counterspies had get suspicious and were recalling him to confront him. If he refused the summons, he would destroy his career. Just if he returned home, he could be shot.

His MI6 handlers assured him they'd picked up no sign anything was wrong. They urged him to go to Moscow, but they as well provided him with an escape plan in case he signaled that he was in danger.

Gordievsky decided to risk his life and go.

**********

Athens, May 21, 1985: Afterward the Tuesday-morning time staff meeting at the Soviet Embassy, Col. Sergei Ivanovich Bokhan stayed behind to talk to his boss, the local rezident of the GRU, the Soviet armed forces intelligence bureau.

As the deputy primary, Bokhan was privy to all GRU spy operations aimed at Hellenic republic, the United States and the other NATO countries. After they chatted for a while, the rezident said, "By the way, Sergei, this cablevision came in" and tossed it over. It said Bokhan's son, Alex, xviii, was having trouble in armed forces school and suggested the deputy have his vacation now, iii months early on, and return to the Soviet Matrimony to deal with him.

Bokhan froze. "Stay calm," he recalls telling himself. "They know."

His boyhood nickname, dorsum on a collective farm in Ukraine, was "Mole." Now a stocky, powerfully built man of 43, he had been working for the GRU for 16 years—and feeding Soviet secrets to the CIA for 10. He knew instantly that the cable was a ruse. But a few days earlier he had chosen his brother-in-police force in Kiev, where Alex was studying, and been bodacious his son was doing well.

Bokhan assumed that both the KGB and the GRU were watching him. He decided to go out Athens—but not for Moscow.

**********

Moscow, August iii, 1985: It was 2 a.m. when Andrei Poleshchuk got home. The 23-twelvemonth-old announcer had been working late for Novosti, the Soviet press agency. Through the windows of the ground-floor apartment he shared with his parents, he could encounter strangers moving about. A large man let him in and flashed a bluecoat.

"Your father'southward been arrested," the man said. He would non say why.

Arrested? Incommunicable. His male parent, Leonid Poleshchuk, was a senior KGB counterintelligence officeholder, near recently the deputy rezident for counterintelligence in Lagos, Nigeria.

For months, Andrei had been hoping his begetter would find him an flat. He had graduated from school and plant a proficient job, and he wanted to live on his own. Housing in Moscow was virtually impossible to detect, even for a KGB officer, just sometime that May, he'd received a seemingly miraculous letter of the alphabet from his father. It said his parents had unexpectedly heard of an flat they could purchase for him; his male parent decided to have his holiday early and come home to close the deal. Leonid and his wife, Lyudmila, had been dorsum two weeks when the KGB showed upwardly at their door.

"It was surreal, like a bad nightmare," Andrei told me. "I could not believe what was happening. I went into the bathroom, locked the door and stared at myself in the mirror."

The KGB men searched the apartment all night. "In the morning, they took us—my mother, my grandmother and me—and put u.s. in split up blackness Volgas," Andrei said. They were driven to the infamous Lefortovo prison for interrogation.

On that first day, Andrei pressed his questioners to explicate why his male parent had been arrested. One of them finally answered: "For espionage."

**********

The twelvemonth 1985 was a ending for U.Due south. and British intelligence agencies. In addition to Gordievsky, Bokhan and Poleshchuk, more than a dozen other sources were exposed. That fall, the KGB rolled up all of the CIA'south assets in the Soviet Wedlock in a lightning strike that sent the bureau reeling. Ten agents were executed and countless others imprisoned.

Faced with these unexplained losses, the CIA in October 1986 fix a small, highly secret mole-hunting unit to uncover the crusade of this disaster. With the abort of Aldrich Ames in 1994, it seemed that the mole hunters had found their quarry. When he began spying for the Russians virtually a decade before, Ames was chief of the CIA'southward Soviet counterintelligence branch, entrusted with secrets that would exist of incalculable value to the KGB. He was well-nigh to exist married, and his debts were mounting.

After Ames was arrested and charged with espionage, his attorney, Plato Cacheris, negotiated a plea bargain with prosecutors: Ames' wife, Rosario, an accomplice in his spying, would be spared a long prison sentence if he cooperated fully with the regime. In extended CIA and FBI debriefings, he talked about his ix years of spying for Moscow—including the twenty-four hour period when he turned over, in his words, the identities of "nigh all Soviet agents of the CIA and other American and strange services known to me."

That twenty-four hour period was June 13, 1985, by Ames' business relationship. In his fourth-floor office at CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, he wrapped up five to seven pounds of secret documents and walked out of the building. He drove across the Potomac River to Washington, D.C. and entered Chadwicks, a popular Georgetown restaurant, where he handed the documents to a Soviet Embassy official named Sergei Chuvakhin. The agents he betrayed that solar day, he has said, included Oleg Gordievsky, whose CIA code proper noun was GTTICKLE; Sergei Bokhan, or GTBLIZZARD; and Leonid Poleshchuk, or GTWEIGH.

But the CIA and FBI debriefers soon recognized a glaring anomaly in Ames' business relationship: It was clear that those iii agents had fallen under suspicion in May 1985—earlier Ames insists he handed over the documents.

"The timeline merely didn't piece of work" to explain Gordievsky'due south recall to Moscow, FBI Special Agent Leslie Wiser, who ran the Ames example, told me. "At to the lowest degree the timeline based on what Ames said when he was debriefed....If it wasn't Ames, then it was someone else, so nosotros began to search for the source of the compromise," Wiser said.

That raised a possibility that remains, fifty-fifty today, a discipline of deep concern amongst counterintelligence agents, a problem privately acknowledged but little discussed publicly: That the 3 agents may have been betrayed by a mole inside U.S. intelligence whose identity is still unknown. The FBI declined to comment on whether the search Wiser began is continuing.

The mere belief that there's another mole, whether correct or not, can cause chaos inside an intelligence agency. During the 1960s, a corrosive mole hunt led by James J. Angleton, the CIA's counterintelligence master, led to institutional paranoia, paralyzed operations aimed at the Soviet Union, and disrupted the lives of many innocent CIA officers who were fired or sidetracked in their careers. And even so to an intelligence agency, ignoring the possibility of a mole isn't really an pick, either. The stories of Oleg Gordievsky, Sergei Bokhan and Leonid Poleshchuk—reported here in all-encompassing new detail and based on interviews with Gordievsky, Bokhan and Andrei Poleshchuk, every bit well as former FBI and CIA officials—suggest the harm a mole can exercise.

**********

As soon as Gordievsky landed in Moscow, he picked up signs that he had gambled wrong. On the front door of his apartment, someone had locked a tertiary lock he never used because he had lost the key; he had to break in. Clearly the KGB had searched his flat.

Some days passed before his boss, Viktor Grushko, drove him to a KGB dacha, saying some people wanted to talk to him. Gordievsky was served sandwiches and Armenian brandy. The adjacent thing he knew, he woke upward half-dressed in one of the dacha'due south bedrooms. He had been drugged. A KGB general told him he had confessed. "Confess once again!" the general roared.

Gordievsky was taken home, but Grushko confronted him at the KGB the adjacent day. "We know very well that yous've been deceiving the states for years," he said. Gordievsky was told his London posting was over, but he would exist allowed to remain in a not-sensitive KGB department in Moscow.

It was apparent that Soviet counterintelligence agents did not nevertheless accept enough evidence to arrest him. Gordievsky believes they were waiting to catch him contacting British intelligence. "They expected I would do something stupid," he told me. But it was simply a matter of time. "Sooner or later they would arrest me."

His escape programme was bound under the flyleaf of a novel; he had to slit the encompass open to read the instructions. He was to stand up on a sure Moscow street corner on a designated twenty-four hours and fourth dimension until he saw a "British-looking" man who was eating something. He did and so, but aught happened. He tried once again, following the fallback plan, and this fourth dimension a man conveying a night-dark-green purse from Harrods, the upscale London department store, walked past eating a processed bar. It was the indicate to launch his escape.

On the appointed day he startedproverka, or "dry-cleaning"—walking an elaborate route to throw off anyone who might be watching him. From a Moscow railroad station, he fabricated his way by train, bus and taxi to a betoken near the Finnish-Soviet border, where he hid in some grass by the roadside until two cars stopped.

Inside were three British intelligence agents—the candy-bar human being and 2 women, one of whom was Gordievsky'southward MI6 case officer in London. Although Gordievsky has written that he climbed into the trunk of ane of the cars, a former CIA officer says he actually crawled into a space in a specially modified Country Rover. Had the Russians examined the auto, they would have seen the hump on the floor where the driveshaft would normally be. But this Land Rover's driveshaft had been rerouted through ane of the vehicle'south doors, the erstwhile CIA officeholder says, so that Gordievsky could fold himself into the hump, in event hiding in plain sight.

They drove through several checkpoints with no trouble, but they had to finish at Soviet customs when they reached the border. When the driver turned off the engine, Gordievsky could hear dogs close by—Alsatians, he later learned. Minutes passed. His fear mounted. He started having trouble animate. The women fed the dogs tater fries to distract them. Then the car started upwards again, and the radio, which had been playing popular music, suddenly boomed out Sibelius'Finlandia. He was free.

**********

In Athens, Bokhan called an emergency telephone number that rang in the CIA station within the American Embassy. He asked for a fictitious Greek employee. "You lot have the incorrect number," he was told.

The coded exchange triggered a meeting that dark with his CIA case officer, Dick Reiser, who cabled headquarters in Langley that BLIZZARD was in trouble. Presently there was a programme for an "exfiltration," the CIA'due south term for spiriting an agent in danger out of a foreign country.

Five days after Bokhan received the cable about his son, he took his wife, Alla, and their ten-twelvemonth-old daughter, Maria, to the embankment. He had never told his wife that he was working for the CIA—it would have put her in mortal danger—but now he had to say something. Equally they walked on the beach that Saturday, he said his career was in problem. Would she ever live in the West?

"What state?" Alla asked.

"It doesn't matter," he said, and quoted a Russian proverb: "S milym rai i v shalashe." If you love somebody, you will have heaven even in a tent.

"I don't want to live in a tent," she said.

He dropped it, sensing that he was getting into dangerous territory. They had a sumptuous lunch—Bokhan knew it might be his terminal meal with his family—and Maria bought a stuffed Greek doll called a patatuff. Later on they collection home, he packed a gym bag and announced that he was going for a jog. Then he kissed his married woman and daughter goodbye.

He drove effectually Athens in his BMW for close to an 60 minutes to make certain he wasn't being followed, then walked into a 100-pes pedestrian tunnel under a highway. Reiser was waiting in a car at the other terminate. In the dorsum seat were a jacket, hat and sunglasses. Bokhan put them on every bit Reiser drove to a safe firm. Afterward dark they left for a small airport, where Bokhan boarded a CIA plane. Later stops in Madrid and Frankfurt, a armed forces jet flew him across the Atlantic. At Andrews Air Forcefulness Base in Maryland he looked out the window and saw several black cars and people on the tarmac. He asked if they were there to greet an important diplomat. "No," he was told, "they're hither for yous."

He walked down the steps and shook hands with the waiting CIA officers.

"Welcome to the United States," 1 of them said.

**********

Afterward months of interrogation at Lefortovo, Andrei Poleshchuk told his captors he wouldn't reply any more than questions unless they told him who his father worked for. "That's when they showed me a slice of newspaper with the words, 'I met Joe,'" Andrei told me. "Information technology was in my father's handwriting." Leonid Poleshchuk knew his beginning CIA instance officeholder, who had recruited him in Nepal, equally Joe. "It was the KGB's way of saying my male parent worked for the CIA," Andrei said.

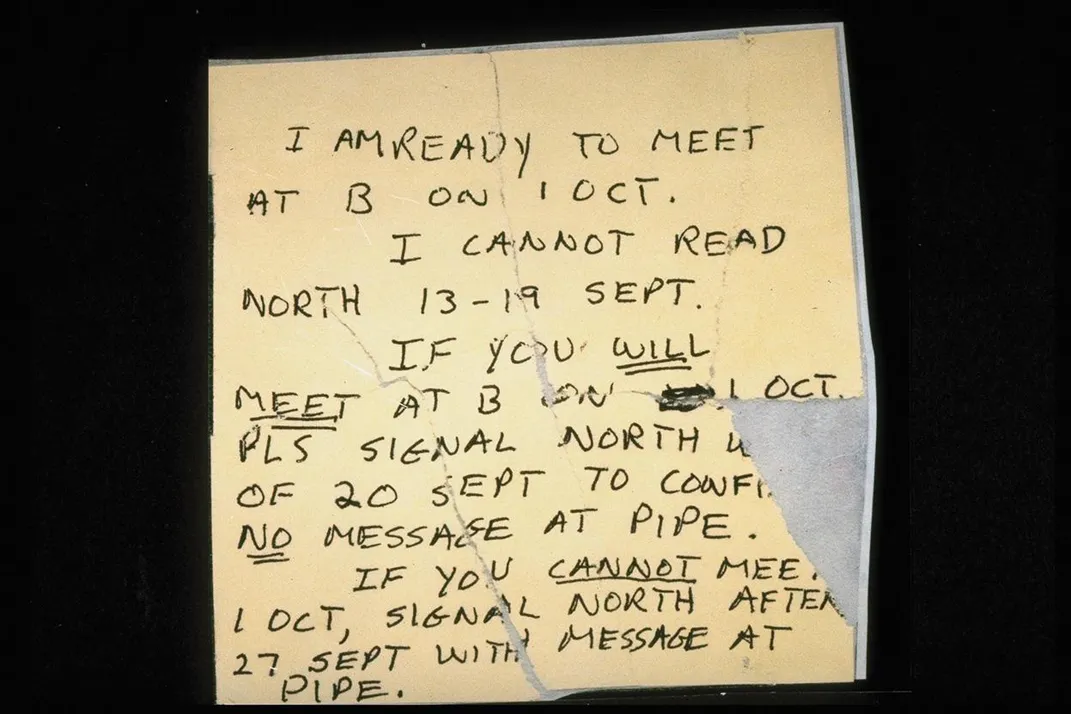

Before Leonid Poleshchuk left Lagos, he had asked the CIA for $20,000 to buy the apartment that was supposedly waiting for him. The agency cautioned that information technology would be likewise risky for him to bring that much greenbacks through the airport and told him the money would exist in Moscow, stashed inside a fake stone.

What neither the CIA nor Poleshchuk knew was that the "flat" was a KGB performance. The Soviets had bundled for the apparent adept news to reach his wife through a friend and former co-worker in Moscow, who wrote to her in Lagos. Poleshchuk was lured back to his fate.

Leonid never made it to the rock, his son said. A Russian Boob tube documentary shows a shadowy figure picking it upwards, but Andrei said it is an actor, not his father.

In June 1986, Leonid was tried and, predictably, bedevilled. Andrei was allowed to visit him in prison house only in one case, later on he was sentenced to death. "At beginning I couldn't even recognize him," Andrei said. "He had lost a lot of weight. He was sparse, stake and evidently sick. He was like a walking expressionless man. I could sense he had been tortured." Leonid was executed on July 30. The KGB told Andrei his begetter'south remains were cremated and there would be no grave.

**********

In the history of U.S. intelligence, merely 3 major moles—men whose betrayals had lethal results—take been identified.

Before Ames, there was Edward Lee Howard, a CIA officer who had been slated to become to Moscow but was fired instead for drug utilize and petty theft. On September 21, 1985, Howard eluded FBI surveillance and escaped into the New Mexico desert with the help of his married woman, Mary, and a pop-upwardly dummy in his car's passenger seat (a technique he had learned in CIA training). Simply the day before, Moscow had announced that a Soviet defence researcher named Adolf G. Tolkachev had been arrested every bit a CIA spy. Inside the CIA, Howard was blamed for Tolkachev'southward unmasking and subsequent execution, although Ames, too, had betrayed the researcher's identity. (Howard, Russian authorities reported in 2002, died of a fall in his KGB dacha nigh Moscow. 1 news account said he had fallen down the stairs and broken his cervix.)

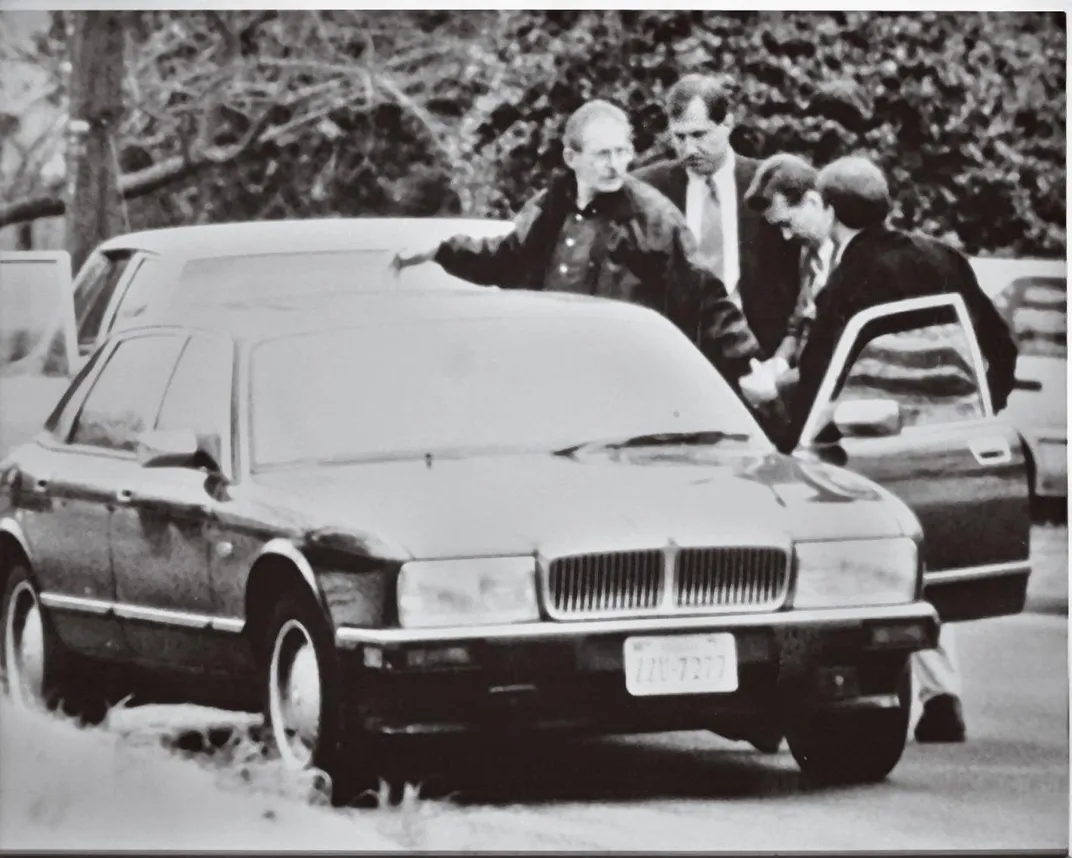

Afterward Ames, there was FBI agent Robert P. Hanssen, who was arrested in 2001. In spying for Moscow on and off over 22 years, Hanssen revealed dozens of secrets, including the eavesdropping tunnel the FBI had dug under the Soviet Embassy in Washington and the identities of 2 FBI sources within the diplomatic mission, who were too executed. Hanssen, who was convicted of espionage, is serving a life sentence in the supermax federal prison house in Florence, Colorado.

U.S. counterintelligence agents take established that neither Howard nor Hanssen had access to the identities of all the American intelligence sources who were betrayed in 1985. So the discrepancy between Ames' timeline and the exposure of Gordievsky, Bokhan and Poleshchuk remains unexplained.

In July 1994, Leslie Wiser, the FBI amanuensis who unmasked Ames, flew to London to interview Gordievsky. The resettled spy told Wiser he was convinced Ames had betrayed him, but he confirmed that he had been abruptly summoned dorsum to Moscow on May 17, 1985—almost four weeks earlier Ames said he named him to the KGB. From the day they talked, Wiser told me, "nosotros believed information technology was important for u.s.a. to consider the strong possibility that Gordievsky was compromised by someone within the U.Southward. intelligence community."

Wiser acknowledges that Ames may have lied or been mistaken about the date—Ames has conceded that he drank heavily before his meetings with the KGB. But Ames always insisted to the FBI, the CIA and the Senate Intelligence Commission that he revealed no meaning sources before his coming together at Chadwicks. In April 1985, he has said, he told a Soviet contact in Washington the names of 2 or three double agents who had approached the CIA but who were actually working for the KGB—"dangles," in intelligence parlance. He did so, he said, to prove his bona fides as a potential KGB mole. In a letter to me from the federal prison in Allenwood, Pennsylvania, where he is serving a life sentence, Ames wrote: "I'one thousand quite sure of my recollection that I gave the KGB no names of any other than the two or three double agents/dangles I provided in April '85, until June 13th."

**********

For those who are betrayed, the impairment persists long later on the initial shock passes. A few days later Oleg Gordievsky was recalled to Moscow, the KGB flew his wife, Leila, and their two daughters there, and he broke the unwelcome news that they would not be posted dorsum to London. "When I came to Moscow, she left," he says, taking the children with her on a vacation.

After Gordievsky escaped, a Soviet war machine tribunal sentenced him to death in absentia. He underwent a debriefing by MI6 and cooperated with it and other Western intelligence services. He traveled ofttimes, to the United States, Germany, France, New Zealand, Commonwealth of australia, South America and the Middle East. He met with British Prime number Government minister Margaret Thatcher and President Ronald Reagan, wrote a memoir and co-wrote a book on the KGB.

He always hoped Leila would bring together him in England. She did, in 1991, just the strain caused by 6 years of separation proved too much to repair. Past 1993 their spousal relationship was over.

Sergei Bokhan was also separated from his family for vi years. Within two weeks after his flight to the United States, he had a new proper name, a false background, a Social Security number and a ix-millimeter Beretta. He stayed in safe houses in Virginia at first, so lived half a year in California to learn English, moved back Due east and consulted for the CIA and some U.S. companies.

When Bokhan escaped from Athens, the KGB hustled his wife dorsum to Moscow, searched her apartment and began a series of interrogations. "For two years I went to Lefortovo two, three times a week," Alla Bokhan told me. "Nosotros had neighbors that were very close. Everyone avoided me. If I was waiting for the lift, they went down the stairs. I had no task. When I plant a job, the KGB called and they fired me. That happened several times."

Finally, in 1991, with the KGB in disarray after its primary led the failed coup against Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, the authorities permit Alla and her daughter exit. They flew to New York and, with assistance from the CIA and the FBI, were reunited with Sergei at a motel well-nigh John F. Kennedy International Airdrome. He had champagne and flowers waiting, a big basket of fruit, chocolates and a balloon. There were embraces, and anybody cried. Maria, then 16, was carrying the patatuff.

Bokhan's son, Alex, also made it to the U.S., in 1995. He works as a estimator programmer. For a long fourth dimension he resented the bear on of his father's CIA spying on his own life. "I was angry considering I was dropped from armed forces school and sent to the Regular army, far off, about Vladivostok," he said. "I was xviii years old." He sees that episode differently at present. "Subsequently many years, I understood him. It'due south OK. To be dead or to be alive was the question for my dad. He didn't have a choice." Today, Sergei and Alla live quietly in the Sun Belt under his new identity.

Andrei Poleshchuk told me his father'south abort was a disaster for his female parent. "It shortened her life," he said. "Presently after his abort she collapsed psychologically. I will never forget the day when I got home and she was singing songs, melodies, no words, and looking insane. Her eyes were empty. It was scary."

The KGB took her to a sanitarium, where she was drugged and interrogated farther. After some months, she was released. But, he adds, "I would never, always run into her smile once more." She died iii years afterward, in 1988.

After his father was executed, Andrei kept working for Novosti. In 1988, he took a Moscow river cruise and met "a blond, bluish-eyed and very beautiful" adult female named Svetlana, who worked for an automotive magazine. They married in 1993, after the collapse of the Soviet Matrimony, and he worked for an independent newspaper in Moscow for a fourth dimension. In 1997, Andrei and Svetlana emigrated to the United States. They have two children, and he works as an independent research annotator for concern and government contractors in Northern Virginia.

Soon after they arrived in the U.s., at that place was a ceremony honoring his father at a Russian Orthodox church in Washington. "Afterward, we drove to a habitation in Virginia for a reception, where I met Joe," Andrei told me in a conversation over lunch at a restaurant tucked away on a side street in Washington. Leonid's original case officer "blamed himself for years for letting my father down. Joe had become very close to my father and worried that some action by him, some fault, had led to his betrayal."

Earlier his begetter left Lagos, Andrei said, he gave a golden spotter to his CIA example officeholder at the fourth dimension. "He asked information technology exist given to Joe, with a message, 'Here is something from Leo.'" By the time Joe learned of the gift, Andrei said, his father had been arrested. "Joe said to his people, 'Go on the watch, I want to give it to his son.'" At a reception after the church ceremony, Joe gave Andrei the picket.

He was wearing it the day we met.

**********

Intelligence agencies cannot tolerate unsolved mysteries and loose ends. Long after the massive losses in 1985, the lingering questions however gnaw at their counterintelligence experts. Milton Bearden, who held several senior posts is his 30-year career at the CIA, is convinced there was a traitor, equally yet undetected.

"Some of it just didn't add together upwardly," he says. "The mole isn't just some guy who stole a few secrets. He might exist expressionless, or he's living in his dacha now. And the intelligence culture is not going to let that get. In that location is no statute of limitations for espionage. These things have to exist run to basis."

If in that location is a quaternary mole, and he is nonetheless alive, the FBI would surely want to take hold of him and prosecute him. The CIA would want to debrief him at length to endeavor to determine the full extent of his treachery. If it should plow out that the mole is no longer alive, the intelligence agencies would however run a harm assessment to try to reconstruct what and whom he might have betrayed.

"That the KGB ran a 'fourth mole' is undeniable," Victor Cherkashin, a wily KGB counterintelligence officer, has written. Of course Cherkashin, who worked in the Soviet Embassy in Washington and handled Ames, may have been unable to resist a chance to taunt the FBI and the CIA.

It is possible that Gordievsky, Bokhan and Poleshchuk fell under KGB suspicion through some operational error or communications intercept. Simply some highly experienced U.South. counterintelligence experts doubt it.

John F. Lewis Jr., a former FBI counterintelligence agent who was chief of the national security segmentation, believes there is a quaternary mole. "I always idea there was another one," he told me. "There were sure anomalies that took place that we just couldn't put our finger on."

And Bearden says, "I remain convinced there is a fourth man. Perchance a fifth. I talked to some old MI6 friends, and they say they are sure there is. Either one of ours or theirs."

More From Smithsonian.com:

When the FBI Spent Decades Hunting for a Soviet Spy on Its Staff

Spy: The Inside Story of How the FBI's Robert Hanssen Betrayed America

baileysqualkinsaid.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/still-unexplained-cold-war-fbi-cia-180956969/

0 Response to "This Bad Boy Can Fit So Much Cold War Arts Funding"

Publicar un comentario